ٻلھڻ نامہ Bulhan Nameh - Dolphin Diaries

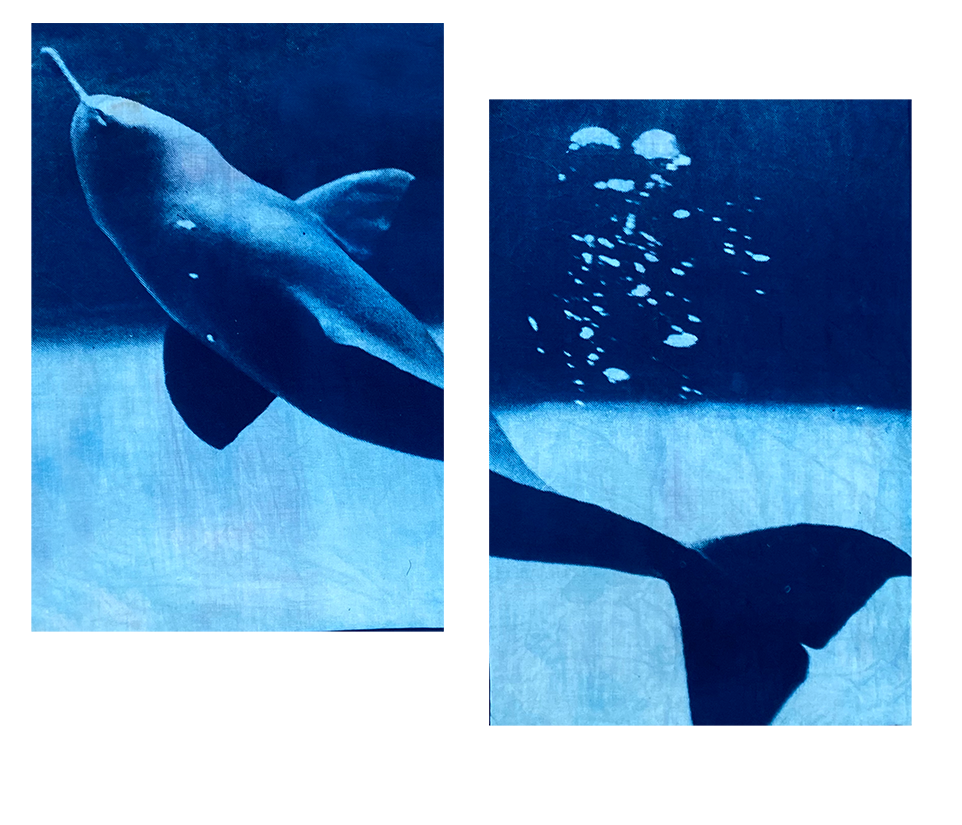

Catching Bubbles 10x16 inches each panel

Diptych, Cyanotype on khaddar fabric, image taken from Giorgio Pillari’s Secrets of the Blind Dolphin

Sindhu Mata on ghariyal/ makar vahana سنڌو ماتا

Digital Print on cotton lawn and khaddar, embroidery thread and sequins, 10x10 inches. 2022

Bulhan Nameh is a long term research based project that looks at a selection of sites on the River Indus between Sukkur and Rohri in Sindh, Pakistan. Taking its name for the Sindhi word for the Indus River Dolphin, bulhan, this series intends to look at how in this 10 km long stretch of river punctuated at one end by the British era Sukkur Barrage and at the other by the island shrine of Khwaja Khizr, known locally to Hindus and Muslims as Zinda Pir. Here wildlife, history and spirituality collide with colonialism, capitalism, feudalism, as well as the ever more present modern state.

Nameh, is a Farsi, Urdu and Sindhi word for diary - this particular diary is written through printmaking and textile. Cyanotypes, analog photographs and archive are paired with traditional Sindhi embroidery as a way to root this project within its current cultural landscape, as well as with memory, nostalgia and a sense of loss. Sukkur is the last place where the river is still full much like She was before the dams and barrages, it is the last refuge of the Indus River Dolphin and a site that evidences syncretic religious practices that still carry on in modern Sindh.

The Indus is personified as Sindhu Mata, a river that not only gave Sindh its name but also India, Hinduism and all derivatives of these words. In my research I do not intend to expose all elements of the river at this location but instead I hope to re-mystify the Indus and in so doing allow us to re-imagine Her as a living and ever changing entity rather than just an exploitable resource.

Sindh, Floods 2022

Khaddar, thread and mirror work. 12x9 inches. 2022

Modern Sindh موجودہ سنڌ

Khaddar, thread and mirror work. 12x9 inches. 2022

Sindh 2,500 BC سنڌ ۲۵۰۰ قابل از مسیح

Khaddar, thread and mirror work. 12x9 inches. 2022

Sindh 250 AD قابل از مسیح ۲۵۰ سنڌ

Khaddar, thread and mirror work. 12x9 inches. 2022

Sindh 750 AD ۷۵۰ سنڌ

Khaddar, thread and mirror work. 12x9 inches. 2022

Sindh 1700 سنڌ ۱۷۰۰

Khaddar, thread and mirror work. 12x9 inches. 2022

The Indus River has never been static, historically each flood changed the course of the river slightly - even today, a satellite image of a cross section of the river from five years ago will look different to one taken last month. This is because rivers are as much sand and mud as they are water, eroding sand from one side and shifting it to another so over a course of a few centuries it may shift several hundreds of miles, making and ending entire civilizations. Its shifting waters are memorialized by the demise of Moen-jo-Daro and the love story that tells of the collapse of the city of Al-Mansur - also known as Brahmanabad.

These six maps show how the river has changed course specifically in the province of Sindh from 2,500 BC to the present day highlighting significant cities of today and yesteryears using the Sindhi tanka. The only constant is Sukkur - shown as a mirror embroidered in place using a button hole stitch as a reference to how radically the river has changed over time. Even this city, with its shrines, temples and ancient forts did not even exist until the 9th or 10th century when the river changed course from Aror, Raja Dahir’s capital, to where it intersects Sukkur today. The delta, shown in green also changes, initially a wide open wetland, similar to that of the Euphrates and Tigris deltas, gradual silt deposition pushed the land further into the sea creating the modern day district of Thatta.

Modern Sindh shows an entirely altered landscape with canals shown via a blanket stitch drawing billions of cusecs of water out of the river and drying up the delta erasing more than fifty percent of Sindh’s mangroves and its delta. The Final map shows the extent of 2022’s disastrous floods but also points to the value of a liberated ecosystem where water is free to drain into the river and finally into the sea, uninhibited by dams, barrages and roads that have essentially blocked natural water pathways.

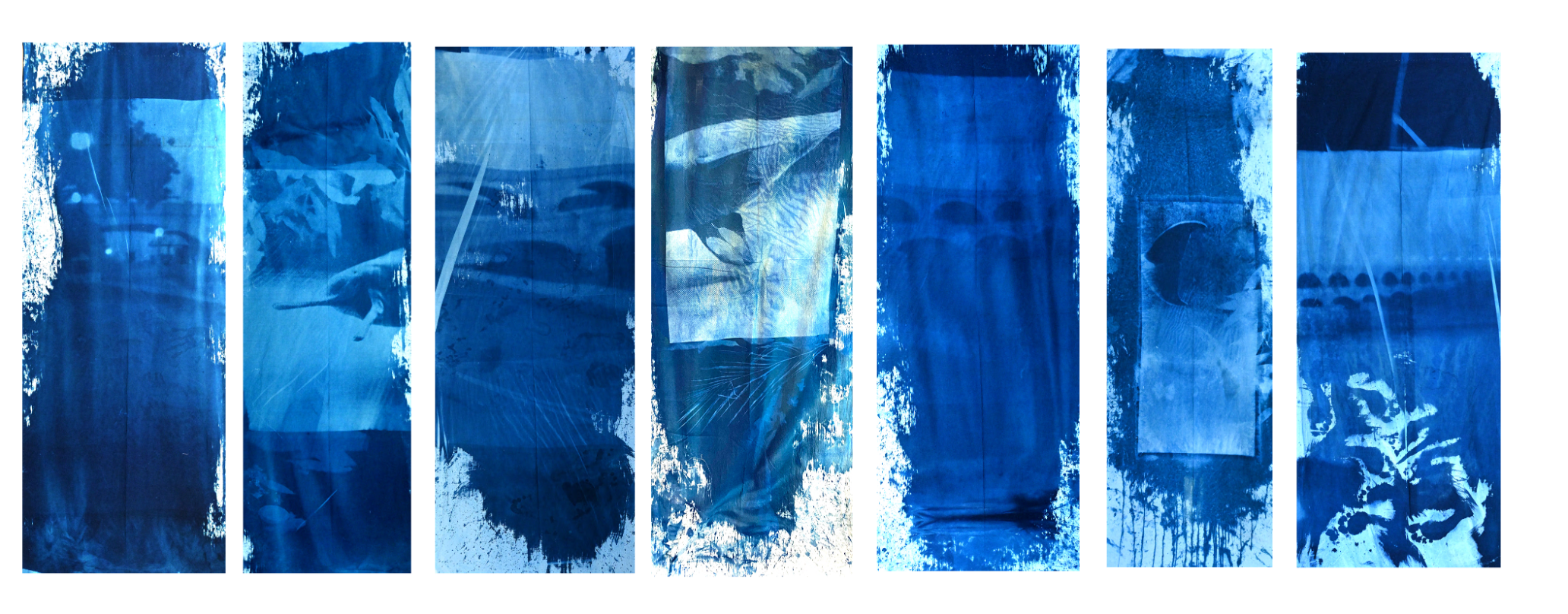

Dammed

Varying Dimensions, 8 piece hanging fabric panels. Cyanotype on khaddar

2022

Built in 1932 Sukkur Barrage is one of 15 barrages (and several more dams) on the Indus that has segmented the Indus River Dolphin into three major population groups, divided by four barrages. From north to south they are: Chashma and Taunsa (170-200 dolphins), Taunsa and Guddu (600), as well as Guddu and Sukkur (1,100-1,400). Smaller populations can be found further north between Jinnah Barrage and Chashma as well as between Sukkur and Kotri.

Research for this piece has come from Dr. Giorgio Pilleri’s Secrets of the Blind Dolphin, and Dr. Uzma Khan and Hamera Aisha’s report, Abundance Survey for Indus River Dolphin published in 2017.

Ellahi, Mirani, Pilleri

Cyanotype on cotton stitched together with embroidery and mirror work on wood, 8ft x 3ft, 2022

In March 2022 a seven foot four inch dolphin was rescued from a canal branch of the Indus River that was in the process of drying up - this was the largest specimen ever measured - that was until April that same year when an eight foot female was rescued from a canal. This piece therefore reflects the average size of a fully grown, mature adult female Indus River Dolphin.

The story told here is that of the relationship between Nazir Mirani’s family and that of the Swiss scientist Giorgio Pilleri. It was Mirani’s father, Karam Ellahi, and two brothers, who kept a small school of river dolphins in a pond attached to the river’s mainstream for an entire year for Pilleri to study. Pilleri decided to take two of these dolphins with him to Berne, Switzerland enlisting the help of the Mirani clan who captured the dolphins, placed them in stretchers and loaded them into trains for Karachi. In Karachi, they were placed in the swimming pool of the Midway Hotel and then loaded onto flights to Zurich. While the dolphins survived the trip they died only a few months into captivity, proving what we know too well that dolphins - river or marine - simply cannot survive outside of their natural habitat.

Though cruel by today’s standards, it was Pilleri’s research that laid the foundation for what we know about the Indus River Dolphin and it was Mirani’s family that facilitated that. This research further informed the Pakistani government in 1972 to make the Indus River Dolphin a protected species and an Indus dolphin reserve was created for their protection.

Research and images for this piece are from Giorgio Pilleri’s, Secrets of the Blind Dolphin

Collaboration With Janan Sindhu, Saahil Ki Kahaniyaan

Janan Sindhu has been Working as independent film director and producer since 2018. Hailing from Khipro in Pakistan’s southern province of Sindh, Sindhu’s work has been focusing on the relationship of the ecological and the social. His most recent documentary – Bulhan: The Blind Dolphin, sheds light on the Indus River Dolphin.

Janan Sindhi at Koel Gallery, behind him is our collaborative Multimedia Piece: Mirani and his dolphins

Video Projection on loop and cyanotype quilt on Multani khaddar backed with velvet, varying dimensions, 2022

This collaboration, which was funded by the British Council via Koel Gallery merged the worlds of textile art and film to highlight the role of Nazir Mirani and his family within dolphin conservation, the effect of barrages and dams on the health of the river, its people and ecosystems, as well as the place of the Indus River Dolphin within Sindh’s cultural Landscape.

Press

Works accentuate importance of Indus River for subcontinent

Syeda Shehrbano Kazim Published February 17, 2022

“Contextualising the river in all its historical, social and cultural nuances, the artist through his work reimagines the Indus as a living, evolving entity. He uses cyanotypes, analogue photographs and archival inkjet prints on khaddar, cotton and muslin fabrics embellished with traditional Sindhi embroidery of threads, mirrors and sequins.

The unusual amalgamation of media helps evoke a sense of both time and space in his work.”

Traversing Indus: Zulfikar Ali Bhutto

Nayha Jehangir Khan Posted on: February 18, 2022

“Engaging with the image making techniques of an older era like archival processing, analog photography and Cyanotype, the artist travels forward and backward through time without hesitation, able to visually manifest a plethora of perspectives. His exploration on the complex spectrum of identity politics is rooted in his long-term research into the region. Each artwork holds the weight of his deconstructing historical, cultural, social and personal experiences.”